Clues to the presence of a port

The excavations in 1899 at the Scoglio del Tonno ('Tuna Rock'), near the present stone bridge 'Sant'Egidio', revealed the presence of Mycenaean materials (a Mediterranean civilisation which was widespread from about 1600 BC to 1100 BC), namely terracotta vases and female idols, as commonly found in Mycenaean sites in Greece.

These Mycenaean finds are proof that the inhabitants of the Aegean frequented the stretch of sea separating Greece from Italy, stopping in all probability at Corcyra (Corfu), which was used as a stopover and storage location.

From these contacts with overseas peoples, the local civilisation was being transformed, creating the conditions for Spartan colonists to one day found Taras.

Sbancamento scoglio del tonno, 1899 (da AA VV, Taranto da una guerra all’altra, Mandese, Taranto 1986)

Idoletto miceneo, 1375-1350 a.C.. Ritrovato a Taranto, Scoglio del Tonno, 1899. (fonte MArTa)

A world of relationships

The Magna-Greek period began around the 8th century B.C. and continued until the 3rd century B.C., when it was the Romans who conquered all the territories of Magna Graecia.

Between the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. Taranto had close trading relations with the main Ionian cities: Syracuse, especially during the rule of Dionysius I (430-367 B.C.) and Dionysius II (397-343 B.C.) and friendly, commercial relations also with Locri, Crotone, Sibari, Heraclea and Metapontum.

It can be assumed, from what Herodotus says in his Histories (IV, 164), that the Tarantines also traded with Cyrene, a Greek colony located near the present-day town of Shahat in eastern Libya…

coins tell the story

Monetary finds bear more direct witness to the commercial influence of the city of Taranto in antiquity. Towards the end of the 4th century BC, Tarentine coinage was widespread in Metapontum, Croton, Reggio, Lucania, Apulia, as far as Picenum and Etruria. Outside Italy, coins minted in Taranto have been found in Lipari and Kefalonia in Greece. They had on one side the prow of the ships and on the other the figure of Taras with trident and shield showing a trophy.

Statere in argento proveniente dalla zecca di Taranto, del 380-345 a.C; dal tesoretto ritrovato a Taranto, Contrada Corti Vecchie, 1916 (fonte MArTa)

The jewellery of Taranto

Around the 4th-3rd centuries B.C., goldsmiths’ workshops were active in the Magna-Greek Taras, producing particularly fine jewellery. The gold and silver probably arrived by sea from the East, partly as a result of the expansionist wars of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). The craftsmen of Taranto reinterpreted the ornamental motifs of Greek output in an original way, thanks also to their use of enamels.

Orecchino a navicella in oro. Seconda metà del IV sec. a.C.; Ritrovamento:Taranto, via Umbria, 1958. (fonte MArTa)

Diadema in oro. Fine del IV - inizi del III sec. a.C.. Ritrovamento: Marina di Ginosa (TA), Contrada Chiaradonna, 1927. (fonte MArTa)

Exported products

From the very beginning, a number of typical Apulian products have left from the port of Taranto: wheat, cereals, oil, wine, fish and salted meats, but also the famous dye for luxury garments, purple...

The production of purple is one of the manufactures linked to the sea that made Taranto famous in Magna Graecia and at the time of the Roman Empire.

The Murici (Bolinus Brandaris, or “spiny-dye murex” mollusc) from which purple is extracted grew well in the Mar Piccolo, enabling this celebrated production then to take place throughout the Mediterranean.

From each individual mollusc, a single drop of colour was extracted. Thousands of drops were needed to make a cloak: purple-dyed fabrics, particularly sought after for their beauty and colour stability, were therefore extremely expensive and remained the preserve of the very wealthy classes.

The precious purple could be used to colour the area’s famous wools, another flourishing business in the Taranto region.

Gusci di murici triturati per l’estrazione della porpora. III-II sec. a.C. proveniente dall’ ex convento di S. Antonio, 2012 (fonte MArTa)

The murici, or 'li cuecc'le'.

Murici, also known as ‘sea snails’ or, in Taranto, ‘Coccioli’ (Cuecc’le), are molluscs with an unmistakable appearance and intense flavour.

They are protected by a thick shell about 6 centimetres long, with a peculiar club shape, narrow at the bottom and wide at the top, where there is a conspicuous opening from which the mollusc is extracted, protected by a calloused foot that allows it to move along the seabed and protect itself.

Today they are still served as an appetiser or can be stewed.

Dettaglio di gusci di murici utilizzati per l’estrazione della porpora. . III-II sec. a.C., provenienti dall’ ex convento di S. Antonio, 2012 (fonte MArTa)

Discovering the places of purple

The discovery of processing vats is noted by a traveller in the second half of the eighteenth century. It is along the eastern shore of the Mar Piccolo, near Villa Peripato, where a hill of snail shards ('Munt d' l' Cueccl') still stands, the waste product of the extraction of purple from these precious molluscs.

In 1766, during his Grand Tour, the German Baron Johann Hermann von RiedeseI (1740-1785) visited the ancient monuments in Taranto in the company of Cataldo Antonio Atenisio Carducci (1733-1775), an expert on ancient artefacts, and wrote

“He showed me outside the city, in a field of grain, a round hole turned upwards, where there are two ducts, one to carry water and the other to make it flow; he believes that this hole was used for the preparation of the colour purple, of which the imprint can still be seen in the walls: moreover, he has observed that very close to there, on the side of the small sea, which was really the ancient port, there is a hill entirely formed of ‘murici’, a shell from which it is known that the ancients drew purple”.

Wealth passes through the port

Historians are aware of a number of mandates issued by Charles of Anjou that give us an understanding of how regular and widespread the trade in cereals, wine and salted meat was. In April 1270, the king sent the Procurator of Puglia (the royal official who supervised customs and state taxes) an order to take charge of the loading of certain quantities of wine owned by the king in various places including Taranto, Bari and Brindisi.

Land routes

The reasons for Taranto’s wealth during the golden age for its maritime trade, namely the Magno-Greek and then the Roman periods, were due not only to its geographical position but also to its road network.

Six major roads led from the port of Taranto, radiating in various directions throughout southern Italy: one of these was the second branch of the Via Appia, which branched off from the main artery at Benevento.

Even in the Middle Ages, between 1150 and 1250, the documents that have come down to us paint a picture of a city that was, overall, economically vibrant and still managed to be an important meeting point for merchants and traders on land and by sea.

Byzantine strategies

In 663 Emperor Constans II (“The Bearded”, 630-668), who wanted to severely limit the reach of the Lombards of the Duchy of Benevento over Apulia, landed at Taranto with an army of thousands of men with mounted squadrons and freed Apulia from the Lombard presence, then set his sights on conquering Benevento.

Undoubtedly, landing at Taranto allowed them to control the two road arteries, the Appia Antica and the Appia Traiana, which were of fundamental importance for taking back Apulia. This shows that the port facilities in Taranto were still efficient, as far as they could have been in those days.

For this operation Constans II prepared a powerful fleet, made up of ships for transporting troops, escort ships, cargo ships and finally horse transports.

Further information

The dromon was the warship in use at this time; it was descended from the less agile Roman liburna and equipped with 100 oarsmen and 50 infantry soldiers, plus about ten men including the commander, helmsman and others. In practice, it had the capacity to carry 160 men. The cargo ships, for provisions and troops, were bulkier and could hold a maximum of 300 men.

The “steed ships” were equipped to transport horses, which entered the ship through a large hatch on the stern side. The special arrangements for the transport of horses were such that no more than 100 were permitted. The American excavations carried out in the agora have allowed us to recover a fair bit of evidence (numerous coins, buckles and horse harnesses with the monogram of Constant II) of the temporary presence of the imperial army.

Medium and large tonnage ships of the 15th century

The Fusta was a type of galley that was slimmer, lighter and faster, and characterised by a smaller draught than the classic war galley, known as the ‘galea sottile’ (‘thin galley’). The fusta is positioned between the ‘thin galley’ and the smaller ‘galeotta’.

Marine industry: fishing

In the Norman-Swabian period (13th century), the Mar Piccolo of Taranto contained “fishponds”, i.e. ‘sea lots’ of varying size, bounded by a piling and located as much in the Mar Grande as in the Mar Piccolo.

These fishponds probably became sea plots for growing mussels, which originally grew naturally in large numbers… as can still be seen today.

Documents also tell us about Tarantine salted anchovies: we know that these were particularly appreciated by the Prince of Salerno, Charles II of Anjou (1254-1309), who had them brought directly to Salerno from Taranto.

Through the eyes of a late 17th-century Tarantine

At the end of the seventeenth century, Tommaso Niccolò D’Aquino, a “Tarantine patrician”, wrote a poem in Latin, “Of the delights of Taranto”, where he celebrates the beauties of Taranto and tells its story, becoming to some extent a testament to an era and environment.

There is an exact description of the places, the observation of customs and traditions in their evolution over time.

It gives an idea of the appearance and working of ancient Taranto where, at that time, a large canal (there was no stone bridge) connected the city’s two ports, the Mar Grande and the Mar Piccolo: the inner one was for the military fleet and the outer one for mercantile traffic with the whole known world, from the Crimea to Egypt, from Spain to Cornwall. It was primarily oil that was shipped out of Taranto, but also many other goods such as wool, sheep, horses, wines, purples and many foods produced in the nearby countryside.

The poem of the mussels and tuna

In his poem on Taranto, D’Aquino describes the fish that inhabit the local seas, and captures the differences between those of the Mar Grande and Mar Piccolo.

He provides valuable information on fishing, taken directly from the fishermen, whose working traditions and rules of life date back to ancient times.

For example, it tells us about tuna (ten pages of description!) and the tuna fishery at Capo San Vito, about fish farming in the fishponds along the coast, about the cultivation (the so-called ‘gardens’) of the legendary Taranto mussels. And it tells of the industries of the sea that have now disappeared: purple and byssus, the production of oysters, for which Taranto was once famous.

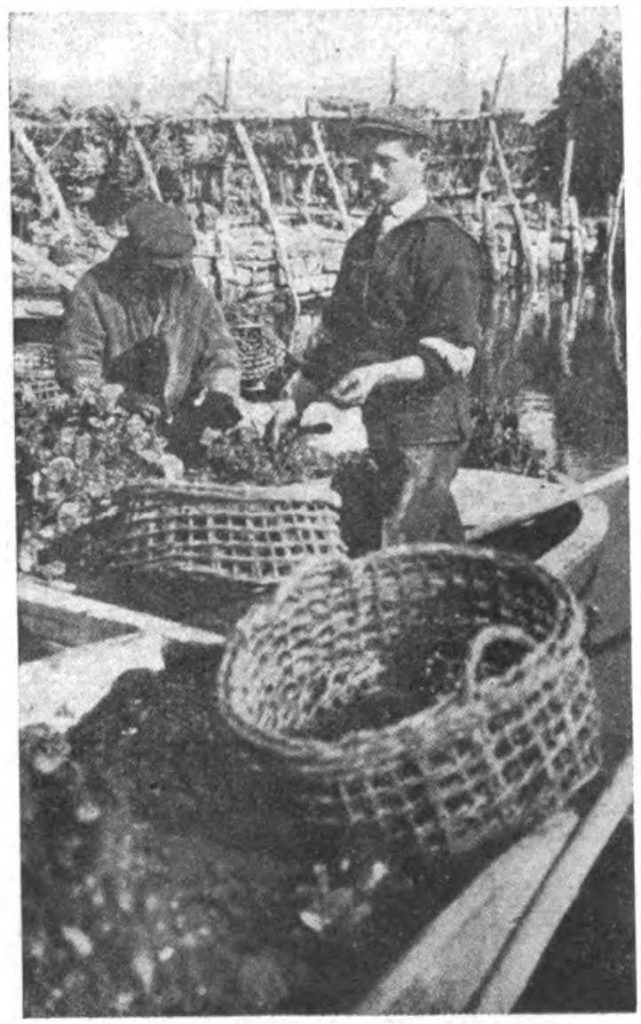

The oyster gardens

In Taranto, oyster farming seems to date back to the 4th century AD. Over time, local oyster farmers developed a unique farming technique that is still practised today, albeit on a limited scale.

In May and June, in the Mar Grande, near the Cheradi Islands, oyster farmers sink bundles of lentisk (a Mediterranean shrub) to a depth of about thirty metres.After about three months, these are brought back to the surface, the twigs on which the oysters are attached, called zippe in slang, are cut off and grafted onto vegetable ropes called libàni;

the ropes are then attached to pergolas, supported by the characteristic chestnut poles fixed to the bottom of the Mar Piccolo, which make up the “sciaie”, veritable marine gardens carefully tended by the so-called “sciaiaruli”.

In the 1920s, 35-40 million oysters were farmed in the waters of the Mar Piccolo alone, a production that was later greatly reduced.

Oyster beds at Punta Pizzone within the Mar Piccolo, Taranto, 1913 (da Rassegna Pugliese di Scienze Lettere ed Arti, vol. XXVIII, January 1913, p.244)

Film Institute of Light, The cultivation of oysters in Taranto, 1951

Meeting point in the ancient Mediterranean

The territory of Taranto has seen the passage and permanent residence of many ethnic groups. Mycenaeans, Spartans and Romans in ancient times, and then the first evidence of the presence of a Jewish community in Taranto dates back to the 4th century AD.

During the Byzantine rule, populations from Greece, Thrace, Cappadocia, Armenia and even Russian-Varegos settled in Apulia and decided to reside permanently in Salento.

The anonymous Lombard who wrote the “Chronicon Salernitanum” visited Taranto in the last months of 839, and the city appeared to him to be closely bound to the sea, crowded with people and prosperous. He tells us of the numerous taverns and markets, where food, wine and pottery were sold.

The Jewish community

The Jewish community was linked to trade (like the Armenian communities), albeit decentralised from the routes to and from the eastern Mediterranean known at this time: they may have participated in the importation of African and oriental products of which there is documentary evidence.

In 1167, according to the Spanish geographer and explorer of Jewish culture Beniamino di Tudela (1130-1173), Taranto was home to a Jewish community of 200 families.

In 1474, the rate of interest that Jews could charge on commercial loans was set at 15 grains per ounce in Taranto, whereas the current rate was 18 or 20 grains per ounce.

The culture of the sea at the table

the frisella is a traditional product, replacing bread because it is more durable and transportable, and was eaten for this reason by sailors on sea voyages.

The name ‘bis-cotto’ tells us that it is baked twice, like doughnuts: during the first baking, halfway through, the friselle are cut with a string. To make them, you just need a few simple ingredients: water, flour (of any kind: durum wheat, barley or other cereals), salt and yeast.

Friselle: in history and legend

It is said that friselle were the bread for Phoenician ships’ voyages, as early as 2000 BC. Although the Phoenicians landed in Apulia several times, legend has it that they were introduced by the Greek hero Aeneas who, in his flight from Troy, is said to have landed near Otranto, bringing with him this strange circular-shaped travelling bread.

At the end of the 13th century, under the Angevins, there were many bakers who supplied the main food for the crews, the so-called ‘fleet biscuit’, made from unrefined flour.

To eat them, sailors soaked them in seawater and seasoned them with olive oil, together with other poor foods such as onions, radishes, dates and dried figs. However, apart from the sailors, the crusaders also appreciated their long life and ease of transport: the circular shape with a hole in the middle allowed them to be tied up and suspended by a string made from agave fibres.