AI PRIMI BORBONE

9.Principality of Balzo Orsini (1420-1463)

9.Principality of Balzo Orsini (1420-1463)

c. 1420

c. 1420

Port taxes.

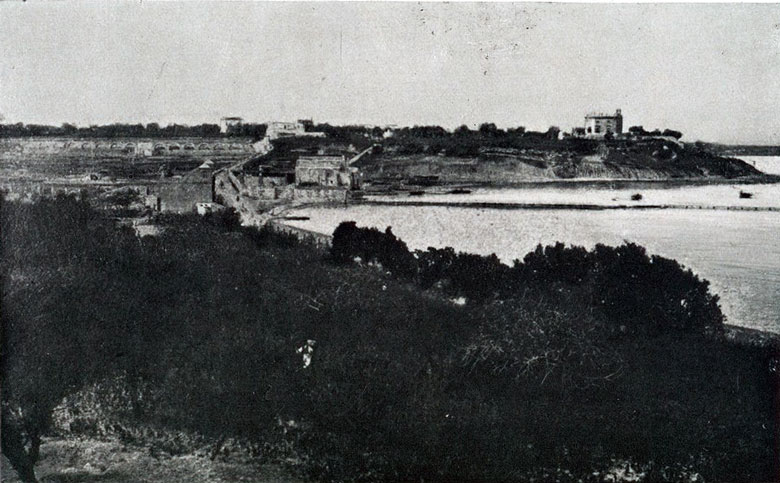

The taxes on movements at the port were: the ''ius platehaticum'', i.e. for the use of public land a percentage was paid on every commodity bought or sold; the ''ius fundici et exiturae'', which was a tax on the storage and export of goods. Then there was the ''cabella cambi''', a tax on all currency exchanges, and a fee for the right of anchorage. Santa Lucia beach, where the port in Mar Piccolo used to be, prior to the construction of the Arsenal. From Rassegna del Comune (Review of the Municipality), 1935, vol. 1-2, www.internetculturale.it

c. 1435

c. 1435

The Fisheries at the time of Prince Balzo Orsini

Prince Giovanni Antonio del Balzo Orsini’s inventory shows that not only were there fisheries throughout the Mar Piccolo, starting from the bridge and the tower above it, but also in the Mar Grande, from Capo San Vito to Patemisco. It specifies which taxes were to be paid according to the types of fish caught, the fishing methods that had to be employed and the permitted fishing periods. Few fisheries were exempt from taxes. Portrait of Giovanni Antonio del Balzo Orsini, Prince of Taranto, taken from Giulio Roscio, Agostino Mascardi, Fabio Leonida, Ottavio Tronsarelli et al., 'Ritratti et elogii di capitani illvstri' (Portraits and Eulogies of Illustrious Leaders), Rome, 1646, p. 128, work released on Google Books under a free licence. http://books.google.com

c. 1440

c. 1440

Salt becomes the privilege of the Aragonese king.

With the arrival of the Aragonese, the production, importation and sale of salt in the Kingdom of Naples became the exclusive privilege of the sovereign. In fact, as early as 1441, King Alfonso the Magnanimous (1393-1458) took possession of the kingdom's main salt pans: Barletta, Castellaneta, Siponto and Taranto. During this period, vast quantities of foodstuffs and fleet biscuits were shipped from the port of Taranto. Illustration by Enzo Nisco from 'La Storia di Taranto Illustrata' (The Illustrated History of Taranto), Scorpione ed., Taranto 2016.

1463

1463

End of the Principality of Taranto.

After the death of Prince Giovanni Antonio del Balzo Orsini (1386-1463), the principality of Taranto returned to the control of the King of Naples, Ferdinand of Aragon (1424-1494). To revive Taranto's economy, the king established a third annual fair, exempt from all tariffs and duties, to be held in the square near the customs house, named after St. Anthony Abbot. In the Accounts of the Treasurer of Taranto, dated 1464, among the foreign merchants who 'warehoused' goods in the port of Taranto were nine Venetian merchants, one from Verona, one from Milan, one from Bergamo and two from Ragusa, i.e. from present-day Dubrovnik. Among the goods stored were iron, wood, linen, velvet, silk, hides from Bulgaria, cheese and pepper. Posthumous portrait of Ferdinand I of Naples, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ritratto_di_Ferrante_d%27Aragona.jpg Artnet.com, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons10. Aragonese Period (1442-1503)

10. Aragonese Period (1442-1503)

c. 1465

c. 1465

With the return of Taranto to the Kingdom of Naples, an economic recovery begins.

In order to kick-start an economic recovery, the citizens of Taranto asked the king for a lower tax burden, starting with the sale of fish, which was Taranto's main economic activity. Other important feudal rights to be adjusted were: the ''ius platehaticum'' (a tax on transactions, i.e. for all goods bought or sold in the public square), the ''ius fundici et exiturae'' (tax on exports), the ''cabella cambi'' (which imposed a fee of one gold coin for every currency exchange) and the anchorage or landing fees, paid according to the type of ship. Model of a Maltese Galley of the Order of the Knights of St. John, Venice Naval History Museum. Myriam Thyes, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

1480

1480

During the Ottoman Invasion of Otranto, several ships sail from Taranto to aid the besieged city.

Four 'onerary' ships (i.e. logistical support vessels, ships supplying water, provisions, etc), as well as a trireme carrying 300 sailors, sailed from Taranto to help Otranto during the Turkish siege. One of these was a Turkish ship sunk in 1469 and subsequently rebuilt in the Taranto shipyards. Detail of the Battle of Otranto by Donato Decumpertino (da Copertino), c. 1550. Capua Castle in Gambatesa (Campobasso). Luxiam, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, Wikimedia Commons

1481-84

1481-84

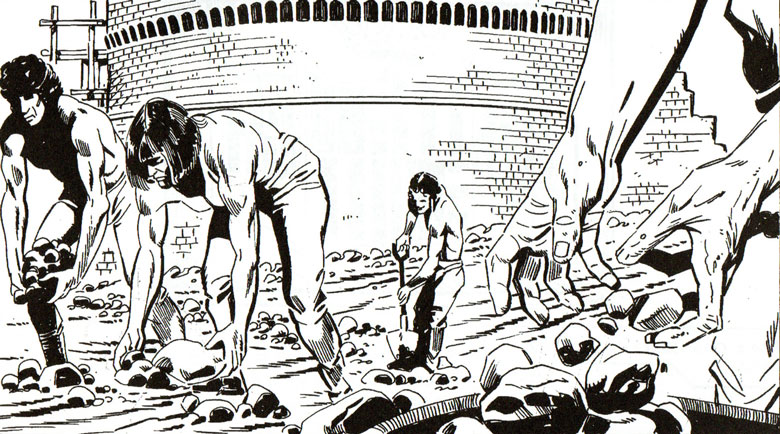

The ‘ditch’ is widened, heralding the navigation canal

Today's navigation canal was only a narrow channel with irregular banks that only allowed the passage of small boats. At that time it was blocked by debris and still followed the design dating back to Roman times. The new channel allowed the passage of larger, heavier ships. It was important because most connections were made by sea. Small and medium coastal shipping was the convenient method of transporting goods. Ships of medium and high tonnage were used, such as fuste, sagitte and caravelle. Illustration by Enzo Nisco from 'La Storia di Taranto Illustrata' (The Illustrated History of Taranto), Scorpione ed., Taranto 2016.

1489

1489

The privileges for shipbuilding

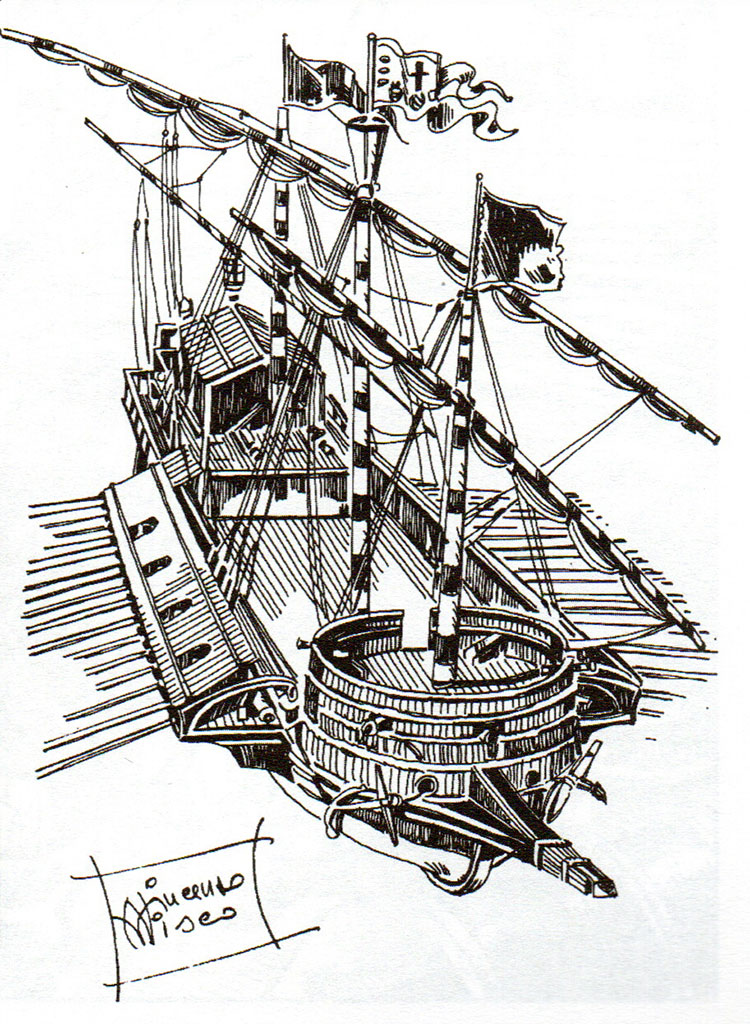

The people of Taranto were granted special privileges over the taxes on the iron, pitch and timber needed to build ships, which allowed them to immediately build ``three beautiful ships of about three hundred botte``, i.e. butts, which was the way to measure the capacity of a ship. Three hundred butts corresponded to a capacity of 84 tonnes. There were also galleys capable of carrying 250 tonnes at that time, but merchant ships of more modest tonnages, that travelled in convoys known as ''mude'' to protect themselves from pirates, were preferred. Those three 'beautiful ships' probably constituted a ``muda`` (single convoy). Pitch used for shipbuilding. Photo Salvatore TomaiDiscovery of America. 1492

Discovery of America. 1492

1492

1492

The Aragonese Castle, one of the symbols of the city, is completed.

Alongside the Aragonese coat of arms quartered with the emblems of Anjou, the plaque set above the 'Porta Paterna' (main entrance) of the Aragonese Castle carries a Latin inscription, which reads: 'King Ferdinand of Aragon, son of the divine Alfonso and grandson of the divine Ferdinand, rebuilt this castle, which was collapsing from old age, in a larger and more solid form, so that it could withstand the impact of projectiles, which it bears with the utmost vigour - 1492.’ Castello Aragonese (The Aragonese Castle), Taranto, 1492. Photo Sergio Malfatti.11. Spanish Period (1503-1707)

11. Spanish Period (1503-1707)

1502-3

1502-3

Ferdinand the Catholic's troops conquer Taranto and the Spanish Viceroyalty begins.

Consalvo di Cordova (1453-1515), the Grand Captain of Ferdinand the Catholic (1452-1516), conquered Taranto and began the Spanish Viceroyalty, a period in which no improvements were made to the Apulian ports. Interest in their condition only revived around 1560, but purely for defensive purposes: fortifying and closing the ports to prevent constant enemy assaults, while completely neglecting the development and preservation of port facilities. Copperplate engraving of Consalvo di Cordova in Aliprando Caprioli, Philippe Thomassin & Jean Turpin, Ritratti di cento capitani illustri con li loro fatti in guerra (Portraits of one hundred illustrious leaders with their deeds in battle), Rome, 1596/1600. Aliprando Caprioli, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

1517

1517

One of the earliest records of the cultivation of black mussels.

The 'fishpond' used for the cultivation of black mussels in the channel, already granted to the city by Ferdinand the Catholic (1452-1516), yielded about 70 ducats (a gold coin of c. 3.5g) a year in 1517. Mussel farmers, 1935 from Rassegna del Comune (Review of the Municipality), year IV, no. 3-4. www.internetculturale.it

1525

1525

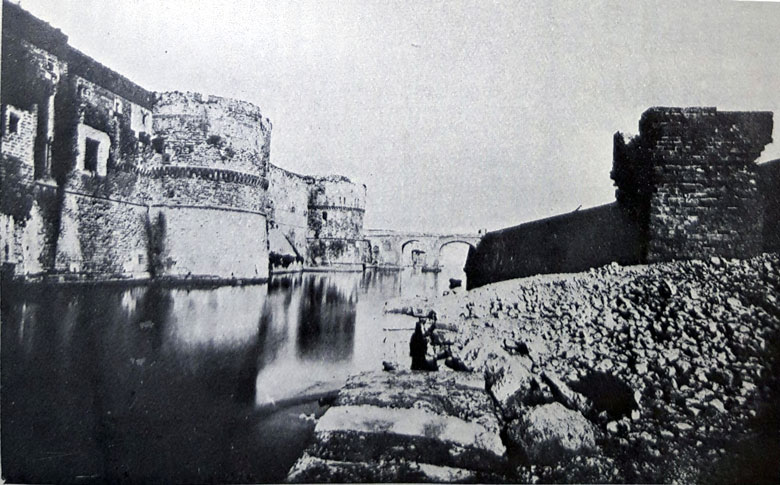

The harbour mouth in the Mar Piccolo goes through cycles of becoming clogged up.

The Dominican Leandro Alberti (1479-1552), passing through Taranto on his journey across Italy in 1525, observed that the mouth of the port was so 'clogged that large ships could not pass through, only small boats'. Fifty years later, the Neapolitan historian Camillo Porzio (1525-1603), in a letter of 1575 to the Viceroy of Naples concerning the condition of the ports of the kingdom, wrote: 'the mouth of the port of Taranto has been filled with stones and soil, so that no large ships can enter'. Moat of the Aragonese Castle, 1869 from Giuseppe Carlo Speziale, Storia militare di Taranto negli ultimi cinque secoli (The Military History of Taranto Over the Last Five Centuries), Bari, Laterza 1930.

c. 1530

c. 1530

Florentine, Venetian and Ragusan merchants.

At this time, Florentine merchants were active in the port of Taranto, exporting wheat to Genoa and Viareggio on Ragusan ships from Dalmatia. This wheat was used to make the 'biscuits' needed by the fleet, or sent to Naples or Spain as part of the annual provision. In addition to this, oil was also exported, mainly to Venice, as well as a modest quantity of spun cotton or 'plush'. Boats drawn on a map of the port of Taranto, c. 1580, Biblioteca Angelica (Angelica Library), Rome. BSNS 56/48

1554

1554

Piracy affects traffic and trade routes.

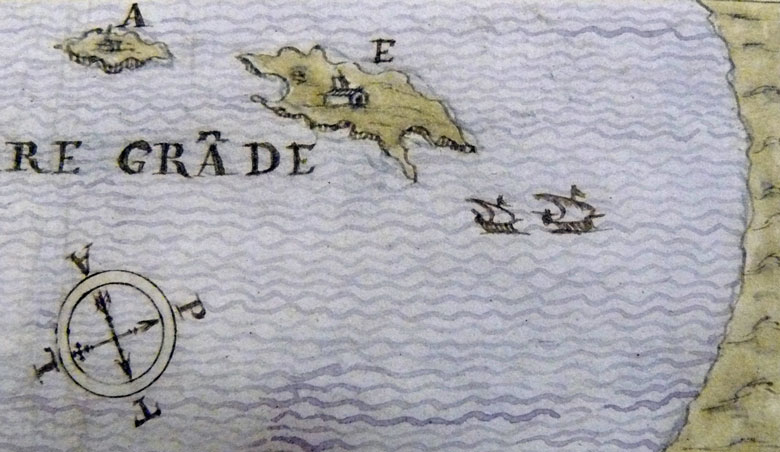

The Turkish pirates Dragut, Ulne-Alì and Curtugul, patrolled the coasts of the Ionian Sea with the aim of capturing all those ships that were sailing along the coast to escape the pirates. Since the Turks needed a safe harbour for their ships, they chose the islands of San Pietro and San Paolo, three miles from Taranto, where they remained for six months. The two islands appear on 16th century maps as St Pelagia and St Andrew, respectively. The Cheradi islands on a map of the port of Taranto, c. 1580, Biblioteca Angelica (Angelica LIbrary), Rome. BSNS 56/68

1571

1571

Logistical base for the Battle of Lepanto.

In preparation for the naval clash between the Muslim fleets of the Ottoman Empire and the Christian fleets of the Holy League, the port of Taranto was chosen as a refuge for all Christian ships. For what would later be known as the Battle of Lepanto, which saw the Papal League victorious, it was the commander-in-chief John of Austria (1547-1578) who wanted the port of Taranto as a refuge for Christian ships before the battle. Illustration by Enzo Nisco from 'La Storia di Taranto Illustrata' (The Illustrated History of Taranto), Scorpione ed., Taranto 2016.

1574

1574

Safe harbour to accommodate a thousand ships.

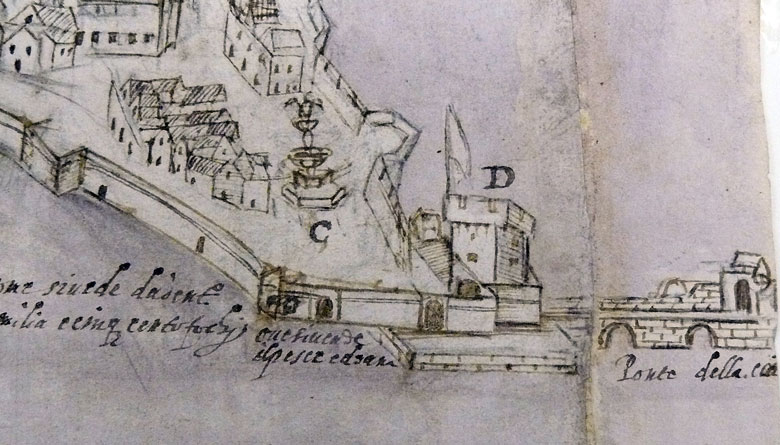

In a long report on the fortifications of Taranto by various royal engineers, it was noted that the mouth of the harbour ``is not well built, because a galley cannot enter through it, for in some parts the bottom is no more than six palms deep, so it will be necessary to excavate it to the completion of twelve palms, and to raise an arch to widen the passage so that at the said mouth remains forty-eight palms wide, so that a galley can enter. Building a bridge over the said channel forty-eight palms long will cost one thousand five hundred ducats``. On the other hand, in the port in the Mar Grande, ``outside said mouth there is a place where a thousand ships can be accommodated, and be secure because from the island inwards it is all safe harbour``. View of the city of Taranto, c. 1580, pen drawing in brown ink and watercolour. Biblioteca Angelica (Angelica Library), Rome. BSNS 56/69.

1647

1647

Masaniello's revolt in Naples over excessive taxes and corrupt rulers.

High customs duties were also imposed on maritime trade, due to the decision to contract out the Viceroyalty's commercial and customs activities to Genoese companies, in exchange for money and warships.The shipping of grain and oil from the port of Taranto took other routes and the excessive taxation helped to fuel smuggling. Portrait of Masaniello by Aniello Falcone - Museo di San Martino, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4403982

1683

1683

Taranto: grain port.

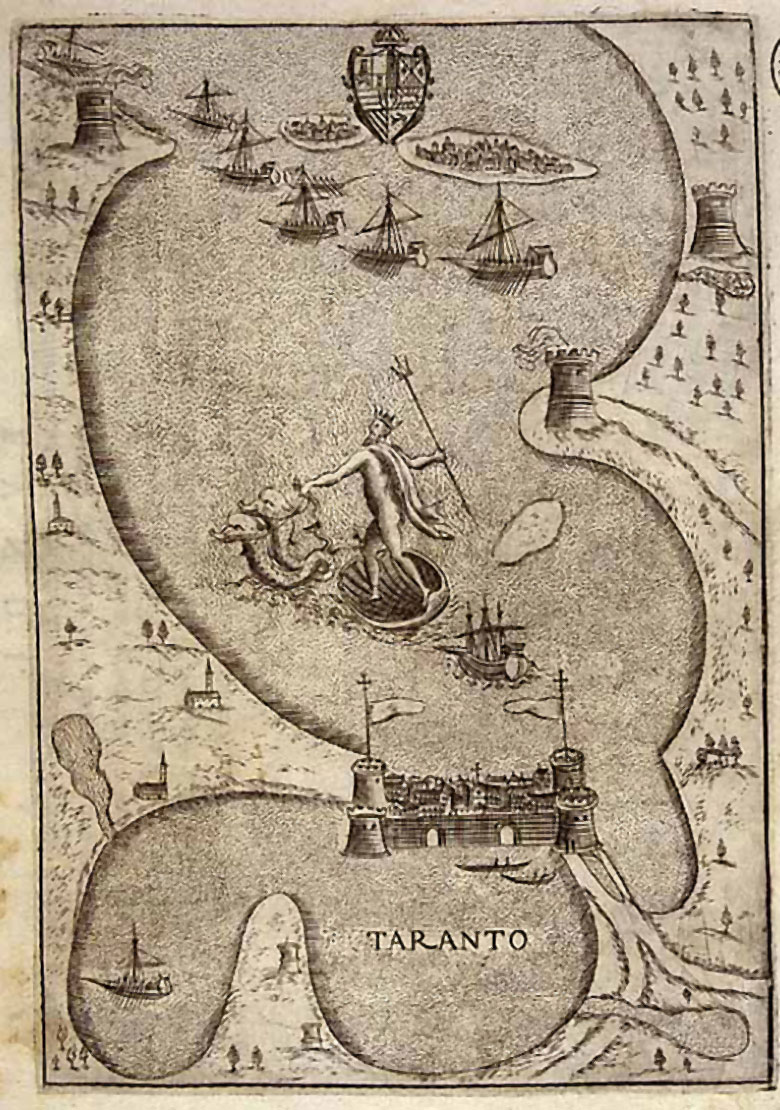

From the port of Taranto, 31,500 «tomoli» of wheat were exported, which almost exclusively served the Neapolitan market. One tomolo corresponded to about 33 kg, so we are talking about 1,040 quintals (104 tonnes) of wheat exported. A modest figure compared to the 5,000-6,600 quintals in the second half of the 18th century, when it became established as a grain port. Map of Taranto with the Mar Piccolo (Little Sea) and Mar Grande (Big Sea), 1600-1699 from Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Library of France), department of maps and plans, GE DD-2987 (5661) – https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53042641h/12. Austrian Period (1707-1734)

12. Austrian Period (1707-1734)

1707

1707

Arrival of the Habsburgs

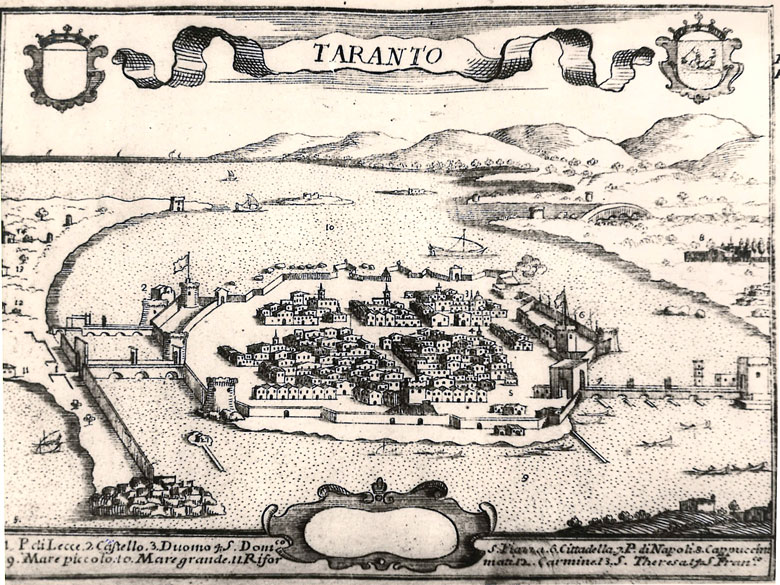

The Habsburgs paid no attention to the commercial use of the ports, neither for trading purposes, nor for supplying the capital. The lack of interest in the Apulian ports could also be attributed to the fact that they were in competition with Trieste, which at that time was beginning to play the role of Austria's maritime outlet in the Mediterranean. View of Taranto from Giovan Battista Pacichelli, Il Regno di Napoli in prospettiva (An Overview of the Kingdom of Naples), part two, Napoli 1703 - Biblioteca Pubblica Arcivescovile ``A. De Leo`` (The Annibale De Leo Archdiocesan Public Library).

1717

1717

Trade routes to Northern Europe

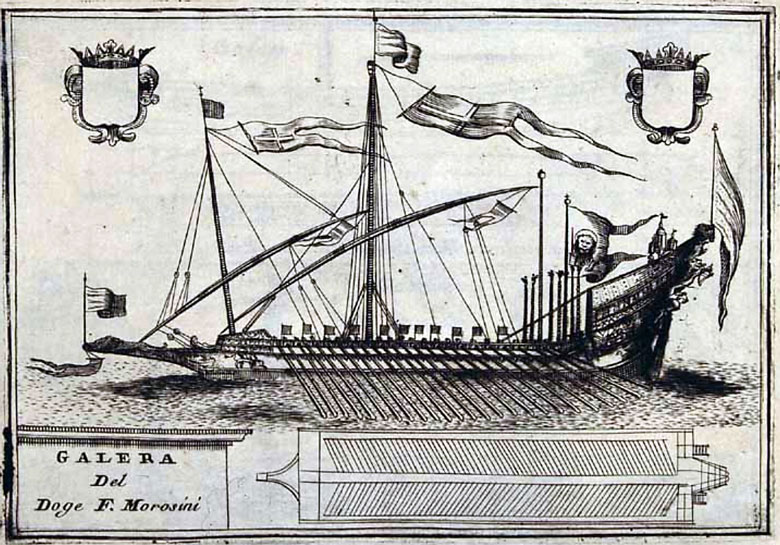

The Tarantine priest Cataldo Antonio Cassinelli, describing Taranto in his Vita di san Cataldo (Life of St Catald), printed in 1717, speaks of the port in the Mar Grande frequented by ships 'not only from Venice, but also from distant countries such as England, Holland, Spain and Portugal, which arrive daily, either to load up with wheat, grain, wine, wool, oil, cheese and shellfish, or to bring new merchandise to sell'.Seafood was so plentiful 'that the Kingdom of Naples and other more distant countries enjoy it; oysters and Tarantine black mussels are so abundant that there were those who compared them to the stars in the sky'. Galley of Doge F. Morosini, from Vincenzo Coronelli, Navi ed altre sorti di barche usate da Nazioni diversi (Ships and other types of boats used by different nations), Marciana National Library - Venice - IT-VE0049 - Public domain – www.internetculturale.it

1721

1721

Death of Thomas Nicholas Aquinas, voice of «Tarantinity» (the quality of being from Taranto).

Tommaso Niccolò D'Aquino (1655-1721), a humanist from Taranto, author of the Latin poem 'Delle delizie tarantine’ («Of the Delights of Taranto», printed posthumously in 1771), where he celebrates the beauties of Taranto. This poem is the testimony of an era; it tells us of Taranto in the early 18th century, with a port in the Mar Piccolo that housed the military fleet, while the port in the Mar Grande was destined, as it always had been, for the merchant trades that went from the Crimea to Egypt, from Spain to Cornwall. There are reports of exports, especially of oil, but also of wine, wool, sheep, horses, purples and many foods that were produced in the nearby countryside. Title page of the book Delle delizie tarantine (Of the Delights of Taranto), by Tommaso Nicolò D'Aquino, Naples, 1771, from http://books.google.com

1732

1732

Oil to Venice

From the testimony of a ship-owner from Taranto regarding a shipwreck off the coast of Tortoreto (Teramo), we know that they brought oil to Venice. In that year, 4,314 salms of oil were exported from the port of Taranto. One «salma» corresponded to 180 kg, so 776 tonnes of oil were exported. For each salma of oil, the port customs demanded 1 ducat. Detail of Piazza Fontana and the Customs House in a View of the City of Taranto, c. 1580, a drawing from the Biblioteca Angelica (Angelica Library) in Rome.13. Primo Periodo borbonico (1734-1801 ca.)

13. Primo Periodo borbonico (1734-1801 ca.)

1734

1734

Improvement of the ports and trade with the coming of the Bourbons.

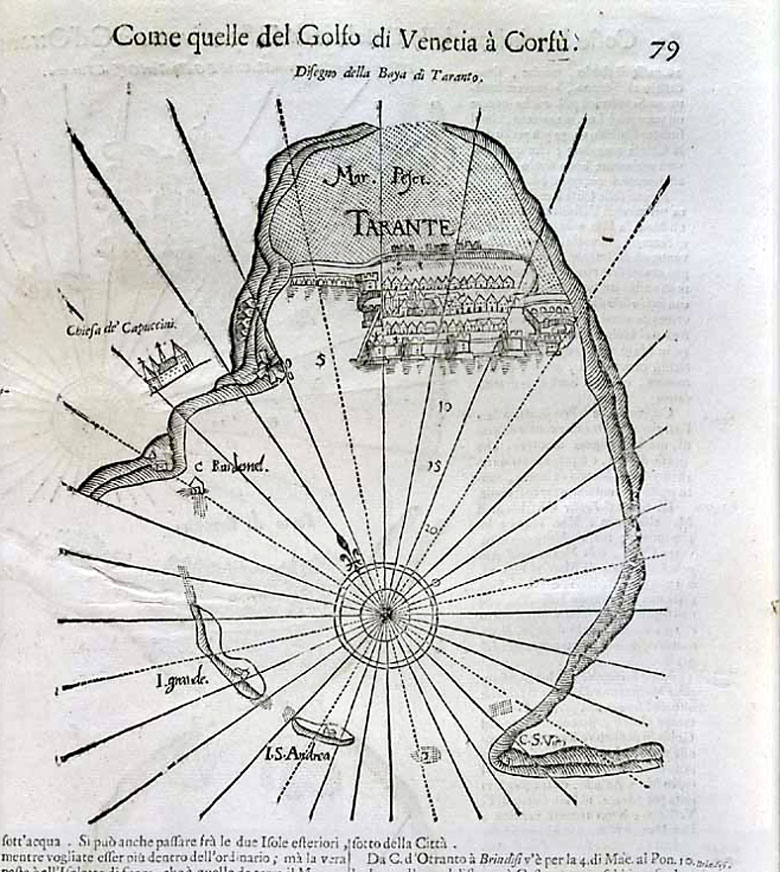

With the arrival of the Bourbons there were concrete attempts to improve the viability of the southern ports. Oil was exported to France and England from the port of Taranto. The bay of Taranto from Specchio del mare (Mirror of the Sea), part one, by Vincenzo Coronelli, 1698, Biblioteca nazionale Marciana - Venezia - IT-VE0049 (Marciana National Library - Venice). Public domain – www.internetculturale.it

1755

1755

Reopening of the canal channel

By order of the King of Naples, Charles III (1716-1788), the canal was reopened to re-establish communication between the waters of the two basins, the Mar Grande and the Mar Piccolo, and thus prevent the loss of the fishing industry. In the port of Taranto, located in the Mar Grande, all the main Apulian products were traded: wheat, oil and wool. Detail of the copperplate engraving map of Taranto drawn by Giovanni Ottone di Berger and engraved by Benedetto Cimarelli, from the printed text by Tommaso N. d'Aquino, 1771. Source: Biblioteca Comunale ``Filippo de Miccolis Angelini`` (The Filippo De Miccolis Angelini Municipal Library) - Putignano - en-ba0112 - Public domain – www.internetculturale.it

1766

1766

In the ancient port, artefacts from the processing of purple.

In his 'Grand Tour', the German baron Johann Hermann von RiedeseI (1740-1785), passing through Taranto in the company of Cataldo Antonio Atenisio Carducci (1733-1775), a connoisseur of antiquities, visited the ancient port located in Mar Piccolo, near the present-day Villa Peripato. There they saw 'a hill entirely formed of «murici», shells from which the ancients are known to have extracted purple; he `{`Carducci`}` believed that this hill was formed over time by the empty shells that the workers of this dye rejected'. Murice shells crushed for the extraction of purple, 3rd-2nd century B.C. Former Convent of St. Anthony, 2012. Museum MArTa Taranto.

1773

1773

Refurbishment of the port’s lighthouse lantern

At the port of Taranto, work is carried out to restore the lantern light, destroyed by a storm. Giovanni Bompiede (†1789), an engineer in the service of the Bourbons, sends a report on the methods to be used to prevent the lantern from rusting. This is the oldest evidence of a lighthouse serving the port of Taranto. Otto Berger's 1771 map shows the warehouses that served the port and the entrance to the harbour between San Vito and the Cheradi islands. Detail of the copperplate engraving map of Taranto drawn by Giovanni Ottone di Berger and engraved by Benedetto Cimarelli, from the printed text by Tommaso N. d'Aquino, 1771. Source: Biblioteca Comunale ``de Miccolis Angelini`` (The Filippo De Miccolis Angelini Municipal Library) - Putignano - en-ba0112 - Public domain – www.internetculturale.it

1774

1774

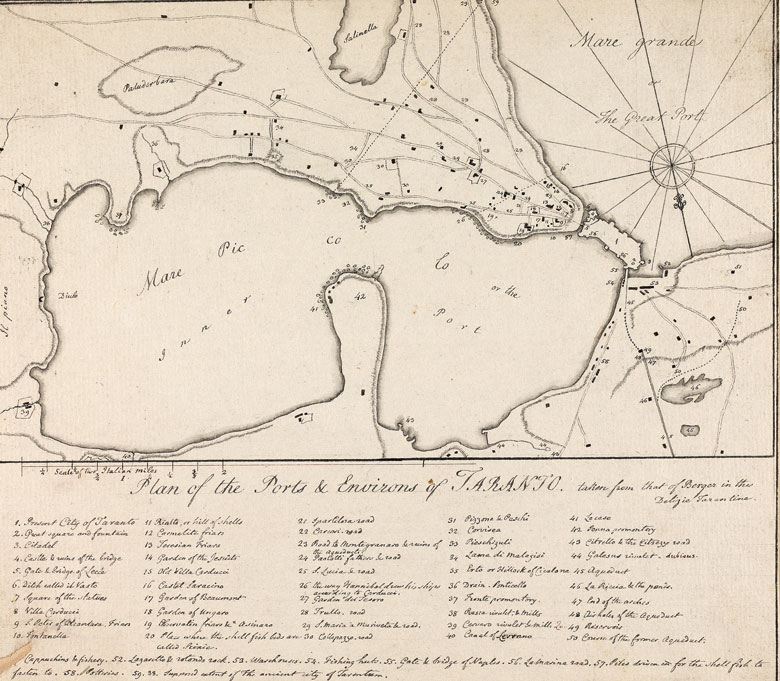

Taranto, the leading grain port under the Bourbons.

Most of the wheat cargoes arriving in Naples came from the port of Taranto: 23 shipments, compared to 13 from the ports of Crotone and Barletta.The trade was, however, the prerogative of wealthy Neapolitan merchants, such as the Berio family, originally from Genoa, who organised the grain trade on Genoese, English, Dutch, Austrian, Catalan and papal vessels. To regulate the trade, an English, an Austrian, a Maltese and a Sicilian consul resided there. The Onciario Cadastra does not mention any Tarantines engaged in trade or any 'sailors', but rather fishermen. Taranto was also one of the destinations of the Grand Tour, as shown by the map made by the English traveller Henry Swinburne (1743-1803) around 1777, copied from the one drawn by Johann Otto Berger in 1771. Map of the port of Taranto and its surroundings, Henry Swinburne, 1777-1779 - Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection - Public Domain https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:29957